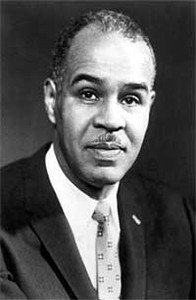

Roy Wilkins (1901-1981) was one of the most important leaders in the civil rights struggle of African Americans.

Born Aug. 30, 1901, in St. Louis, Missouri, of struggling African American parents, Roy Wilkins received his bachelor of arts degree from the University of Minnesota in 1923. During his college career he served as secretary to the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), beginning a relationship which became his career. As managing editor of the Call, a militant African American weekly newspaper in Kansas City, he attracted the attention of the NAACP national leadership through vigorously opposing the reelection of a segregationist senator.

Born Aug. 30, 1901, in St. Louis, Missouri, of struggling African American parents, Roy Wilkins received his bachelor of arts degree from the University of Minnesota in 1923. During his college career he served as secretary to the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), beginning a relationship which became his career. As managing editor of the Call, a militant African American weekly newspaper in Kansas City, he attracted the attention of the NAACP national leadership through vigorously opposing the reelection of a segregationist senator.

In 1931 Wilkins became assistant executive secretary at NAACP National Headquarters. His first assignment, to investigate charges of discrimination on a federally financed flood control project in Mississippi in 1932, led to congressional action for improvement. The first of his few arrests on behalf of equal rights occurred in 1934 when he picketed the U.S. attorney general's office for omitting the subject of lynching from a national conference on crime.

From 1934 to 1949 Wilkins served as editor of the Crisis, the official organ of the NAACP. He was chairman of the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization in 1949. This organization, composed of more than 100 national and local groups, was responsible for sending over 4,000 delegates to Washington in January 1950 to lobby for fair employment and other civil rights.

Wilkins became the NAACP's administrator of internal affairs in 1950, and in 1955 the Board of Directors unanimously elected him executive secretary. This was a postion he held until 1977. When Wilkins began, he played a key role in helping plan and implement ways to eliminate segregation on all fronts and advance African Americans to first-class citizenship. He conferred with presidents, congressmen, and Cabinet officials. Furthermore, Wilkins testified before congressional committees, appeared on television and radio, addressed innumerable groups, and wrote extensively for both the African American press and general publications.

An articulate speaker and accomplished writer and organizer, Wilkins condemned the idea that African Americans must earn their rights through good behavior. He emphatically stated that no American is required to earn rights because human rights come from God, and his citizenship rights come from the Constitution. In support of President John Kennedy's civil rights bill, he testified in 1963 that African Americans "are in a mood to wait no longer, at least not to wait patiently, and silently and inactively." He was chairman of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, which led the civil rights march on Washington in 1963.

Wilkins won the NAACP's Spingarn Medal for distinguished service in civil rights in 1964 and received the Medal of Freedom from President Richard Nixon in 1969. He received honorary degrees and awards from 21 universities and colleges. President Lyndon Johnson named him a member of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders in 1967.

In 1968 Wilkins announced a new plan to harness the energies and talents of young African American activists while maintaining a firm line against those who counseled violence and separation. Wilkins stood firmly against these militant movements, and he encouraged the NAACP not to back them either. By 1969 he was being vilified as an "Uncle Tom" by some African Americans and even found himself on the assassination list of one revolutionary group. "No matter how endlessly they try to explain it," Wilkins told Reader 's Digest, "the term 'black power' means anti-white power. [It is] a reverse Mississippi, a reverse Hitler, a reverse Ku Klux Klan."

At the sixty-first annual NAACP meeting in 1970, he warned that "there can be no compromise with the evil of segregation", meanwhile calling upon African Americans to reject separatism and join to build a single society with common opportunity.

He chose to keep his position as executive director year after year, even when high-ranking members of the organization asked him to step down. Wilkins never groomed a successor for his job and refused until 1976 even to court the idea of retirement. When he finally did leave his post in 1977, he was more or less forced to do so by the board of directors, who accused him off-the-record of mismanaging funds. Others supported Wilkins until the end, convinced that without his charismatic leadership, the NAACP would splinter into competing groups with separate directors.

Wilkins' health had been good for many years following surgery for cancer in 1946, but he began to decline in 1980. He died September 9, 1981, of kidney failure aggravated by heart trouble. Wilkins was eulogized by his successor as executive director of the NAACP, Dr. Benjamin Hooks. Hooks told the New York Times, "Mr. Wilkins was a towering figure in American history and during the time he headed the NAACP. It was during this crucial period that the association was faced with some of its most serious challenges and the whole landscape of the black condition in America was changed, radically, for the better." Jesse Jackson also praised Wilkins in the New York Times as "a man of integrity, intelligence and courage who, with his broad shoulders, bore more than his share of responsibility for our and the nation's advancement."

Wilkins' lifelong devotion to civil rights was fueled by a passion for justice. As he stated in his autobiography, he sought to fight against "a deep, unreasoning, savagely cruel refusal by too many white people to accept a simple, inescapable truth - the only master race is the human race, and we are all, by the grace of God, members of it." Years after his death, Wilkins remained one of the most respected voices in the battle for racial equality in the United States. He received numerous awards, including the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, bestowed upon him by Lyndon Johnson in 1969, and the Congressional Gold Medal, bestowed posthumously in 1984.